I give my heart to Jesus and Mary with you in love. Please pray the healing rosary for

our founder, it is helping. We must have faith and see things working out. We must be

united to the Mass at every moment. My heart is deeply connected to all of you. I am

forever grateful for you and all you do for Jesus. We must stay united with Jesus in the

Mass--all day. We pray always in union with the Masses going on around the world. Sunday

is the Sabbath day. We must unite to all these Masses. We need to pray if only for a few

moments on the hour united, with each other, pray especially for our founder and grace and

funds, pray through the intercession of Our Lady of Clearwater. Read the daily messages,

even if some of the writings are profound. God will enlighten our minds if we read with an

open heart, we will receive a treasure from Him when we read and pray to the Holy Spirit.

God is revealing things to us all the time, a little at a time as we read the daily

messages. The writings of our founder will take us to a new depth of understanding the

Divine Mysteries. Don't ask for explanations, let God work in His words. Pray to the Holy

Spirit for enlightenment. Read all that is given and try to give yourself more to God at

Mass and in prayer and in everything you do, offering your lives as a sacrifice. Oh I love

all of you so dearly and I feel closer to you, more than ever before. We have a big date

coming up December 17, 2000. We must prepare our hearts for a special coming of Christ

alive in us. Pray for FAITH and HOPE and LOVE and PURITY. God is so good to us. I thank

God for all of you, His beloved apostles. I thank Him and love you all so much. Just think

how much God loves us. He just loves us so much. We must see ourselves as being so loved

by God and realize more and more, God really loves us. We are so special to Him. He has a

unique calling for each of us to help reach so many souls. It is wonderful when someone

dies and we can look at all the people that person has touched in his life. We must pray

for the schools and teachers. Please pray for St. Xavier, it is a big Jesuit school with

so many boys, so many priests could come from there if Jesus called them and they prepared

the boys for this. Oh I love you so much and I love the Jesuits. Jesus gave us Father, our

founder, from the Society of Jesus. I pray through the intercession of St. Ignatius and

St. Xavier and St. Claude de la Columbiere and St. Robert and St. Aloysius and all the

popes and priests in heaven. Pray to St. Joseph, too. God loves us so much.

On one Hail Mary bead or as many as you desire, say: (this is given for Fr. Carter, you

can replace your loved one's name).

Pray the Hail Mary or Hail Mary's then pray this after the Hail Mary.

After the Glory Be— pray the following petition.

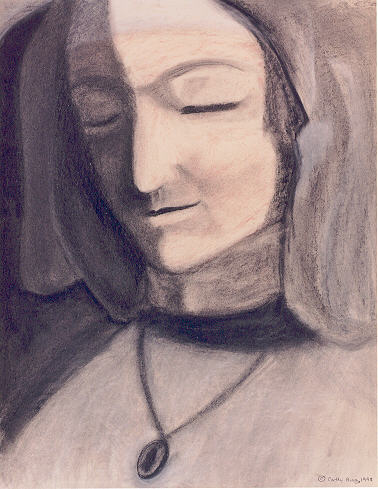

Note: You can look at Mary on the image rosary while you pray this rosary.

See the altar of sacrifice.

See the priest offer sacrifice to God.

See Lucia's vision.

See the Father and the Holy Spirit and the most pure, sinless, human person - Mary

stands by the altar with her Immaculate Heart.

See Lucia, a human person tainted by sin beneath the altar.

See the grace and mercy as she saw in the vision flowing from Christ, the Mediator,

between us and God.

At every Mass we offer the bread and wine, and listen to the words at the Mass.

The bread and wine are changed to His Body and His Blood through the hands of the

priest.

We want our offering, our sacrifice to be a most pleasing offering to the Father.

We offer sacrifice to the Deity for our sins.

At every Mass see that we are coming to God to offer the most pleasing sacrifice to the

Father, the sacrifice of His Son, Jesus, for our sins.

We want to make reparation to our God for our sins.

Now carry this one step further--in the Morning Offering we unite everything we do as a

sacrifice (an offering), united to this most pleasing sacrifice, offered to the Father in

all the Masses going on around the world.

TO BE AN INTERCESSOR FOR THE PRIESTS, THE CHURCH, AND THE WORLD.

A most pleasing sacrifice, offered for our sins and the sins of the world.

The words of the Mass are so beautiful.

We see how we tell God we are sorry for our sins in the beginning of Mass. We want to

offer a pure sacrifice.

The priest washes his hands at the offertory.

We help in the act of redemption by uniting to the Mass.

Now I refer to our founder's chapter on the Mass.

The last 5 days we have presented an in depth discussion by our founder, from his book,

Response in Christ.

It must be studied and read and reread and one must pray for grace to understand what

God is revealing through his writing. Reading his book will help us understand, more and

more, insight into the divine mysteries.

So too, all should study the chapter on grace presented October 16, 2000. Study these

two chapters.

God speaks to us through them.

The life of grace just described expresses itself most perfectly in the

Church's liturgy, and at the same time it is from the liturgy that the Christian chiefly

derives strength for his life in Christ. Central to the Church's liturgy are the

sacraments, and, most especially, the eucharistic sacrifice.

1.

The Sacraments in General

A sacrament is a

visible sign of an invisible, divine reality. Christ, therefore, is the primordial

sacrament given to men by God. In His historical existence Christ was the visible,

tangible manifestation that God has irrevocably entered the world of man with His

merciful, salvific grace. At the same time Christ contained within Himself this divine

reality which He externally manifested.1

We

have previously described the Church as the continuation of Christ. Consequently, flowing

from the idea of Christ as primordial sacrament, the Church is also a sacrament. The

Church continues the visible presence of Christ which was attached to His historical

existence. The Church, through her union with the glorified Christ, both externally

symbolizes and contains within herself the divine reality of God's grace which has been

irrevocably communicated to man.

The Church as

sacrament is a perduring reality. This perduring sacramentality of the Church is

actualized in a special manner through the seven sacraments. As the Church is the general,

visible continuation of Christ's Incarnation, so the individual sacraments can be

considered as particular, visible extensions of Christ's Incarnation.

It is evident,

therefore, why the sacraments are special encounters with Christ. For Christ unites

Himself with the sacramental sign as He offers His grace to the recipient of the

sacraments. In this sense Christ and His sacraments become one. The sacrament and its

minister are merely instruments which Christ employs to give Himself anew. The primary

sacramental encounter is between Christ and the Christian.

Christ offers

Himself to men through the Church and her sacraments so that men may become ever more

united to Him. This incorporation into Christ begins at baptism, through which the

Christian is made both a member of Christ and a member of His Church. This incorporation

into the life of Christ means primarily to be incorporated into His paschal mystery, since

death-resurrection was the essential and summary mystery of Christ's life. It was the

central mystery whereby He gave us life. It is the central mystery which the Christian

must relive in Christ.

Each of the

sacraments deepens our incorporation into Christ's death-resurrection. Each achieves this

in a somewhat different manner according to the primary purpose of each sacrament.

Finally, and very importantly, each of the sacraments deepens this incorporation into

Christ within an ecclesial framework. The sacraments, because they are the sacraments of

Christ and His Church, intensify the Christian's relationship not only with Christ,

but also with the members of the Church, and ultimately with all men.

The

death-resurrection of Christ, encountered in a special way through the sacraments, is most

especially renewed in the eucharistic sacrifice. Thus we can see the logical connection

between the sacraments and the Mass. All of the sacraments point to the Mass. All of them,

according to their own particular finalities, allow for a more perfect participation in

Christ's paschal mystery as sacramentally renewed in the eucharistic liturgy.

2. The Mass

How is the paschal

mystery and all the related mysteries of Christ renewed in the Mass? As a preliminary step to answering this question,

let us first give a more detailed analysis of the mystery of Christ which was briefly

described in the chapter on the Church. Put very briefly, this mystery is God's concrete

plan of redemption centered in Christ. The expansion of this idea leads to the theology of

mysteries, a much discussed topic since the time of Casel.

The following is

one manner in which we may conceive of the mystery of Christ. God Himself is ultimately

the mystery – holy, completely transcendent, completely other.

God in His inner life is thus hidden to man, unless He chooses to reveal and communicate

Himself. He has so acted, giving Himself to man in word and action in Christ. Thus,

because the ultimate mystery, God Himself, has communicated Himself in Christ, we have the

mystery of Christ, the Christian mystery. It is legitimate to speak in the plural,

designating the mysteries of Christ rather than simply mystery, because all that Christ

did was part of the one unified mystery. In all the events of Christ's life God was

communicating Himself and redeeming man in Christ.

There

are other ways of describing the mystery of Christ, yet we find a common denominator in

our original statement: the mystery is God's concrete plan of redemption in Christ.

How is this

mystery of Christ contained in the liturgy? We can explain this presence as follows.2 Christ's mystery of redemption has a

twofold aspect, one temporal and historical, the other eternal. We first consider the

historical, temporal aspect of this mystery.

Christ

is God present among us in human form, the entry of eternity into time. Because of

Christ's humanity, the acts He performed while on earth were subject to the limits of

temporal historicity. Consequently, the unique historicity of these acts of Christ cannot

be repeated, even sacramentally; no, not even by God Himself. This would be asking the

impossible of God, for to reproduce a past act now in its temporal

historicity is a contradiction in terms. Hence Casel's theory of sacramental presence

cannot be held if it posits an exact reproduction of temporal historicity.3

Granted,

then, the temporal-not-to-be-repeated aspect of Christ's earthly life and actions, there

is another aspect to be considered. Christ, although possessing two natures, is only one

person, and that divine. Consequently, the historical redemptive acts of Christ are the

acts of a divine person. Necessarily, then, these acts partake of the eternity of the

divine person and therefore are perennial. They endure eternally in the glorified Christ.4

Through

the medium of His glorified body, this eternal aspect of Christ's redemptive acts can be

made present sacramentally. In the eucharistic liturgy the very person of the glorified

Christ, containing within Himself all His redemptive acts, is sacramentally present. In

very brief form we see the manner in which all the mysteries of Christ's life are

reproduced in the eucharistic liturgy. It is within the Mass, then, the heart of the

liturgy, that the Christian encounters the person of Christ and His mysteries. This

encounter takes place chiefly through the medium of the theological virtues. In faith,

hope and love the Christian, encountering the eucharistic Christ, receives the

supernatural strength to reproduce Christ in Himself. For through contact with Christ in

the eucharist, the Christian receives the grace to relive Christ's mysteries in his own

life. How true it is to say that the liturgy, centered in the Mass, is aimed at

transformation in Christ.

Granted

the primary importance of the Mass, we will now examine in greater detail the eucharistic

sacrifice. In discussing the mystery of Christ and its presence in the eucharistic

liturgy, we have already said much concerning the Mass. Yet we believe a schematically

complete outline of the Mass will provide a more desirable framework for our purpose of

demonstrating the Christian's eucharistic participation, a participation which is at the

heart of contemporary spirituality.

Our

presentation will necessarily be only relatively schematic. At the same time we hope it

will not be superficial. We will make a fourfold division, for we believe this is

necessary for an intelligent discussion of liturgical participation. First, we will treat

of the notion of sacrifice in general. Then we will consider Christ's sacrifice within the

framework of sacrifice in general. Next we will treat of the sacrifice of the Mass.

Finally, we will consider in some detail the individual's participation in the eucharistic

sacrifice.

a)

Sacrifice in General

There are various ways of developing the structure of sacrifice. Some

authors include more constituent elements than others. We will give a structure which we

believe includes the essential elements commonly given. This structure of sacrifice is a

traditional one, yet it is one which can well be harmonized with modern theological,

liturgical and scriptural studies. A leading scripture scholar, F. X. Durrwell, gives us

assurance on this point by telling us of the value of considering Christ's redemptive

activity within the traditional structure of sacrifice developed over the centuries:

"But first it will be useful to look once more at the drama of the Redemption,

placing it in a framework – a framework adequate to contain its rich reality which

God Himself had prepared throughout the history of mankind: Sacrifice."5

We enter upon our discussion of sacrifice in general by considering the first of five

constituent elements.

1) Interior Oblation

The first duty of man is to surrender himself to God out of love. This

fact flows from the truth that God is the Creator and man is His creature. Man, if he is

ideally to fulfill his creaturely role must respond as perfectly as possible to the loving

demands of His Creator. God asks that man give himself completely to Himself. This is only

proper since everything that man has, whether of the natural or supernatural order, has

been given to him by God. Man, in turn, perfects himself by developing these various gifts

according to God's will or, in other words, by giving himself completely to God. Man's

gift of self to God is centered in loving conformity to the divine will. Consequently, one

can understand why the will with its decision-making capacity is the crucial faculty in

man, a point emphasized by contemporary thought.

Man directs himself to God by the virtue of

religion. This is not to say that this particular virtue ranks above the theological

virtues of faith, hope and charity. These are the most excellent, since they unite man

directly to God. We are merely stating that the virtue of religion directs all man's

actions to the honor of God.6

This virtue consists especially in acts of

adoration, thanksgiving, petition and reparation. These interior acts can manifest

themselves in many ways, but they are especially expressed through sacrifice. Here, then,

we have the first constituent element of sacrifice: man's interior offering of himself to

God. This giving takes place chiefly in man's will, under the guidance of the virtue of

religion. This first element of sacrifice is of prime importance, for it deals with

interior dispositions. This importance can be recognized concretely in the history of

religion. For example, the Jewish people were convinced that the principal value of

sacrifice was centered in the dispositions of the people.7

2) Exterior Offering

Man is not a pure spirit. He is a rational animal, composed of body and

soul. Consequently, he desires to manifest exteriorly and concretely the interior offering

of himself which has been made to God in the first movement of sacrifice. He does this by

the exterior offering to God of some material gift. Such a gift symbolizes the interior

offering of man himself. St. Augustine says: "A visible sacrifice, therefore, is a

sacrament or sacred sign of an invisible sacrifice."8

Justification of this exterior oblation is

also found in the fact that man is not only in part a corporeal being, but also a social

being. It is fitting therefore that man exteriorize his interior gift of self in order

that he may give worship to God in a social manner. For his exteriorization enables many

to partake in the sacrificial ritual.

This exteriorization of his inner offering

also helps man to deepen his interior acts. Precisely because man is a composite being,

his various exterior acts of worship can profoundly influence, among others, his interior

acts of love, adoration, thanksgiving, reparation and petition.

Here, then, we have the second constituent

element of sacrifice: the external, ritual giving to God of some material gift which

symbolizes man's interior offering of himself.

3) Immolation of the Victim

In the history of religion there is contained a third element of

sacrifice, that of immolation. In order to make the external offering worthy of God, man

has been accustomed to accompany his offering with a ritual that removes the external gift

from profane use. The victim is immolated so that its former existence might cease, and

that it can thus become something sacred to God. This immolation should not be looked upon

as a destruction, but as a fitting preparation of the external gift. Such a preparation is

the negative element in the transferral process of the gift from profane use to divine

ownership.9 But because the external gift symbolizes the gift of man himself,

the consecration to God of this external gift through immolation represents the

consecration of man himself to God. In other words, the immolation has a special

significance by indicating man's union with God.

Within this consideration of immolation it

will be profitable for us to refer to three basic types of sacrifice common to the Jews of

the Old Law. Such a consideration will have its special significance in our treatment of

Christ's sacrifice. The three sacrifices in question are those of the paschal lamb, of the

covenant, and of expiation or atonement. In our initial chapter we discussed the first two

types. It is sufficient to recall here that each of these, through sacrificial blood, was

instrumental in uniting the Jews with Yahweh as His people. The blood of the paschal lamb

contributed to the Jewish exodus from Egypt, an exodus which attained upon Mount Sinai a

central point of its progress toward the promised land. Here upon Mount Sinai the

sacrifice of the covenant took place as the blood sealed the new life relationship between

Yahweh and the Jews.

In the sacrifice of expiation or atonement we

again see the key role of sacrificial blood. In this sacrifice the blood was sprinkled

seven times over the propitiatory. The purpose of this was to purify the sanctuary from

all the sins of Israel. In turn the altar was sprinkled seven times with blood in order to

achieve its purification and sanctification.

The purpose of the sacrifice of expiation or

atonement, then, was purification and divine reunion. The land of Israel together with the

tabernacle, the altar, the sanctuary and the throne of Israel, had been stained by the

sins of the Chosen People. Through these sins God had been driven from their midst. In the

sacrifice of expiation God returns to Israel through the purification of the tabernacle.

The tabernacle symbolized the souls of the Jews, so we note that God returns to a purified

people. Here we see a simultaneity of purification and reunion.10

Taking together these three main sacrifices of

the pasch, covenant, and expiation, we see the role of the shedding of blood in the

history of the Israelites. The shedding of blood purified and united to God, and indeed

played a most positive role.

4) Acceptance of the Sacrifice by

God

In order that the sacrifice might reach its extrinsic consummation God

on His part must accept it. God's acceptance of sacrifice has been shown in various ways.

Among the Hebrews assurance of the divine acceptance was seen in the phenomenon of fire

falling from heaven and consuming the victim of sacrifice. In the absence of such a

heavenly token, there was at least some assurance that God accepted the sacrifice because

of the duly consecrated altar itself. The altar received the gifts of sacrifice, and in

doing so symbolized God's acceptance of the same.

5) Partaking of the Sacrificial

Victim

In the history of sacrifice men have habitually shown a desire to

accept God's invitation to partake of the offered victim. God must invite men to

participation in the sacrificial meal, for the victim of sacrifice becomes divine

property, and the use of it contrary to the divine will is sacrilegious. If God is pleased

to admit His friends to the divine banquet, this is a manifestation of the divine

goodness.

Since the victim has in a certain way become

divine through its being offered to God, the partaking of this victim has a deep

significance. Through such a participation in the divine banquet one shares in the

sanctity of the victim.11 This sharing in the holiness of the victim is

actually a participation in God's sanctity, since the victim is holy with the holiness of

God to whom it has been offered.

Thus the cycle of sacrifice has been

completed. The interior giving on the part of those offering the sacrifice, exteriorized

and symbolized by the ritual offering of an immolated victim, has brought down from on

high a divine communication.

We have briefly seen the general economy of

sacrifice, the authenticity of which has been borne out by history. This structure of

sacrifice is authentic because it is partly rooted in the very nature of man. At the same

time, this structure has been modified by the demands of positive law. With this general

structure of sacrifice serving as a background, we are now in a position to consider the

sacrifice of Our Lord Jesus Christ, and finally, that of the Mass.

b) Christ's Sacrifice

We will consider Christ's sacrifice according to the same constituent

elements of sacrifice already discussed. In this treatment we will follow the theory of

the unicists, who hold that Our Lord offered only one complete sacrifice as opposed to the

dualist theory which says Christ offered two complete sacrifices, one at the Last Supper,

and one on Calvary. The Church allows either position. We prefer to follow the position of

the unicists, since this seems to give a greater unity to Christ's sacrifice, and indeed

to the total mystery of Christ. This profound unity of Christ's mystery has become more

and more apparent with the scriptural, liturgical and theological renewals.12

1) The Interior

offering of Our Lord

The sacrifice which Christ offered for the redemption of the world was

first and foremost an interior moral act. Christ's life possessed its great value because

of His interior dispositions. His entire life was a constant gift of Himself in love to

the Father and to mankind, and Calvary was the supreme expression of this gift. This gift

of self was regulated by a perfect conformity to His Father's will.

Christ not only was constantly living out this

interior disposition of sacrifice, but He strove to inculcate the necessity of it in the

Jews of His time. He constantly opposed a false and legalistic concentration on the mere

externals of Jewish purifications, for such an attitude tended to diminish the necessary

internal dispositions. The synoptic theology of sacrifice stresses this attitude of

Christ. Bernard Cooke states: "This insistence of Jesus on internal dispositions

characterizes the Synoptic theology of sacrifice, which continues and completes the

prophetic emphasis on the moral and individual aspect of sacrifice. . . . One must

be careful, however, not to exaggerate the opposition (either in the prophets or in the

Synoptic Gospels) between cult and internal dispositions of soul."13

2) Ritual

Oblation

As we have said, man, because of his corporeal and social nature, has

always desired to express the interior oblation of sacrifice in an external, ritual

oblation. So it was with Christ. Unlike the dualists, who maintain that Christ's interior

offering was sufficiently exteriorized during the passion itself, the unicists maintain

that the only place where we can locate a ritual oblation is at the Last Supper. This

ritual oblation cannot be found in any other phase of Christ's sacrifice – from the

Garden to the Cross – despite the efforts of some to do so. Notice, too, that in the

case of Christ's sacrifice, the ritual oblation of the Last Supper is of a

victim-to-be-immolated rather than of a victim already immolated.

Christ's ritual oblation at the Last Supper

possessed a many-faceted signification. We will comment on several aspects. We begin by

recalling the social implications of the ritual oblation. This social element is present

in Christ's actions at the Supper. He told the Apostles to do what He was doing in

commemoration of Him. This would assure that in the future the head and members of

the Church would sacramentally renew Christ's redemptive, sacrificial act. In this manner

the members of Christ's Body would not passively receive the graces of Christ's sacrifice,

but rather would assimilate these graces by actively entering into Christ's act of

atonement. Consequently, Christ's sacrifice, in its perennial, sacramental renewal down

through the ages, was to be of a social, corporate nature.

Closely related to this social aspect of

Christ's actions were the covenant significations of the Last Supper ritual. This is

brought out by observing the connection of Christ's actions with two of the chief types of

Jewish sacrifices we have previously mentioned, the sacrifice of the pasch and that of

covenant. In both of these the concept of sacrificial blood enters in.

The Last Supper was a paschal meal, or at

least had a paschal significance. The Jewish paschal meal commemorated the Jewish people's

delivery from Egyptian slavery, which, in turn, symbolized their deliverance from sin. The

enslaved Jews had been freed from Egyptian tyranny with the aid of the blood of the

paschal lamb. For this blood, we recall, had exempted Jewish homes from the visit of the

exterminating angel. How fitting, then, that at the paschal supper Christ instituted the

eucharist in which His blood is sacramentally shed. He is the new paschal lamb whose blood

frees us not from Egyptian slavery but from slavery to sin. The old pasch, a covenant

communion between Yahweh and His chosen people whom He delivered from Egypt, gives way to

the new pasch, the new covenant communion between God and His people.

These ideas concerning covenant lead us to a

consideration of the second type of Jewish sacrifice linked with Christ's actions at the

Last Supper. We recall that in the sacrifice of the covenant Moses sprinkled sacrificial

blood on both the altar representing Yahweh and the people. This blood, considered to be

source of life, united Yahweh and His people in a union, a common life, or, in other

words, a covenant. We understand, consequently, the deep significance of Christ's words at

the Last Supper when He referred to His blood as being that of the new covenant. This is

the blood which establishes between God and men a new union, a new covenant.

3) Immolation

of the Victim

The central importance of Christ's sacrificial blood is evident. It is

the blood of the new paschal lamb. It is the blood of the new covenant, the blood which

redeems man. The shedding of this blood occurred during the immolation of Christ's

passion-death. Schillebeeckx points out the significance of this immolation in blood:

"The Blood of Christ is a theme that is truly central in the primitive Church, as

Scripture shows it to us. This death sanctifies mankind, reconciles, establishes peace,

redeems, constitutes the Church, and therefore unites man in communion with God and his

fellow men. We are redeemed in sanguine, through the blood of Christ – this we

find on almost every page of Scripture. It is impossible therefore to spiritualize

Christ's sacrifice, to make it merely an internal act of love. There was indeed the act of

love, but it was embodied in the sacrifice of blood."14

At this point we also note the profound unity

of Christ's sacrifice. We observe that priest and victim are one and the same. At the Last

Supper, Christ is chiefly priest; on Calvary, He is chiefly victim. Yet He is always

priest and victim. Christ does not perform the immolation. He rather endures it. However,

this is sufficient since it is not necessary for the priest of the sacrifice to achieve

the immolation himself.

4) The Father's

Acceptance of Christ's Sacrifice

We have demonstrated that one of the constituent elements of sacrifice

is its acceptance by God. In the case of Christ's sacrifice, this acceptance by the Father

was accomplished in a most glorious fashion – through Christ's Resurrection and

Ascension. The Father glorified His Son for the perfect, whole-hearted sacrifice of

Calvary. This glorification shall endure for all eternity, since Christ reigns at the

right hand of the Father as eternal victim, as eternal, glorified victim. Through this

glorified Christ the treasures of His sacrifice are distributed to all men: "Christ's

glorification is the mystery whereby the treasures of his divinity flow to us, through the

opening of his mortal life."15

In the union of these last two elements of Christ's sacrifice,

His immolation in death and the acceptance of His sacrifice through the Resurrection and

Ascension, lies the essence of Christ's redemptive act – of course, in saying this we

presuppose the first element of Christ's sacrifice, His interior disposition or oblation;

this is the essential element. This union of Christ's death and Resurrection is

called His paschal mystery, His passover. In what did this passover or transition consist?

In our initial chapter we briefly described this passover of Christ. We will now expand to

some extent upon this basic reality of Christ's life.

The divine love, or agape, descended into this world for the

salvation of men. This saving force manifested itself to men through the redemptive

activity of the Word made flesh. By becoming man, Christ, although free from sin,

submitted Himself to the conditions and circumstances of a sinful world. His redemptive

activity consisted in a struggle with the forces of evil. As this struggle developed,

Christ at the same time was returning to the glory of His Father. He finally conquered

completely through His paschal mystery. Through His death He liberated Himself completely

from a world impregnated with sin and passed over into the new order of the Resurrection.

Moreover, Christ experienced this transition process not just for Himself. By His own

passover Christ achieved for all men the opportunity to pass from death to life, from a

life of sin to a new life as sons of God. In the words of Lyonnet, "The redemption is

essentially the return of humanity to God. The return is accomplished first of all in

Christ who died and rose again as the first fruits of this humanity (objective

redemption), and then in each Christian who dies and rises again with Christ in baptism

(subjective redemption)."16

Consequently, we have observed, in terms of sacrificial elements,

the most intimate union which exists between Christ's death and Resurrection. They are

inseparable, and lie at the heart of the total mystery of Christ. This paschal mystery is

central, therefore, to the liturgy and to the whole Christian life.

5) The Banquet in Christ's

Sacrifice

The cycle of sacrifice is strikingly completed by God graciously extending an invitation

to partake of the offered victim. This element of sacrifice is miraculously fulfilled in

Christ's oblation. By the words of consecration the bread and wine become Christ. In this

manner Christ gives Himself to His disciples at the Last Supper. We will further develop

these ideas of eucharistic communion in our consideration of the Mass.

We hereby complete the consideration of the elements of Christ's

sacrifice. According to the unicists there was but one sacrifice of Christ. The Last

Supper, death and Resurrection each contributed essential elements. This one sacrifice of

Christ endures in its efficacy for all time. In itself it is not to be repeated. Its

sacramental renewal, however, is repeated daily on our altars in the Mass.

c) The Sacrifice of the Mass

Some contemporary authors, while not necessarily de-emphasizing the

sacrificial nature of the Mass, are giving a renewed emphasis to the concept of the Mass

as banquet or meal. This is all to the good, as long as the sacrificial structure is not

allowed to recede to the background. In this regard it is well for us to recall the mind

of the early Church. Jungmann says: "The first centuries of Christianity, which had

built the framework for the celebration of the Eucharist which is still followed today,

had laid down two basic thoughts: The Mass is the memorial of the Lord, and it is the

sacrifice of the Church. These two thoughts are expressed just as clearly and simply

today: '. . . calling to mind the blessed passion – we offer to your sovereign

majesty – this pure sacrifice.' "17

We should always unite the concepts of the

Mass as sacrifice and the Mass as meal by realizing that the eucharistic meal is an

integral part of the sacrifice. It is its conclusion.

We should also be aware that the Mass is a

covenant sacrifice. It is the sacramental renewal of Christ's covenant sacrifice. The Mass

is the central act of our covenant life in Christ, and therefore it embraces the four

great dimensions of covenant love. In Christ, by the action of the Holy Spirit, we open

ourselves in a special manner during the eucharistic liturgy to the Father's love and we

respond to that love. In Christ and His Spirit we also pledge ourselves at Mass to go out

in a deeper love to the members of the People of God and to all men. We also commit

ourselves anew to be open in receiving the love of others. According to these various

perspectives, the Mass above all is an action of love.

1) Interior Oblation of the Mass

The chief priest and victim of the Mass is the same as the priest and

victim of the Last Supper and Calvary, Christ Himself. Christ makes this interior offering

of Himself in the Mass for the same ends as were present in His own unique sacrifice

– adoration, thanksgiving, petition and satisfaction.

However, Christ is not the only priest at the

Mass as He was at the Last Supper and upon Calvary. All the members of the Mystical Body

are priests along with Christ. To be sure, there is a difference between the hierarchical

priesthood of bishops and priests and the universal priesthood of the faithful. This

difference is one of essence and not merely degree. The point we wish to stress, however,

is that the universal priesthood is a real participation in Christ's priesthood given

through the sacraments of baptism and confirmation.

This concept of the priesthood of all the

Church's members is being stressed today in a special manner.18 Jungmann, the

outstanding liturgical theologian, gives us reasons why this concept of universal

priesthood became relatively obscure for so many years. He states that the concept of the

Mass as the Church's sacrifice faded into the background as a result of the Reformation.

The Reformers maintained that there was only one sacrifice, the one which Christ offered

upon Calvary. To counteract this heresy the Council of Trent and the theology consequent

to it had to clarify that the Mass is a true sacrifice, but not an absolutely independent

one. It is a sacrifice relative to the absolute one of Calvary and a representation of it.

It was emphasized that the priest of Calvary is also the chief priest of the Mass. Because

of such doctrinal controversies, the concept that Christ offers the Mass was alone

considered important. The concept that the Mass is also the sacrifice of the Church

practically disappeared. Finally, Jungmann notes that today we are returning to the

balanced view which meaningfully recognizes that the Mass is not only the sacrifice of

Christ, but also that of the Church.19 This stress on the Church's part in the

Mass is logically connected with the contemporary emphasis on the priesthood of all the

members of the People of God.

As Christ is not the only priest of the Mass,

neither is He the only victim. Again, all the members of the Church are victims along with

Christ. Various Church documents attest to this. For instance, Pope Paul VI officially

calls attention to this: "It is a pleasure to add another point particularly

conducive to shed light on the mystery of the Church, that it is the whole Church which,

in union with Christ functioning as Priest and Victim, offers the Sacrifice of the Mass

and is offered in it."20 Therefore, the members of the People of God,

united as priests to Christ the high priest, offer a combined victim to the Father: Christ

and themselves. Such then in all its deep meaning and beauty is the first sacrificial

element of the Mass.

2) Ritual Oblation of the Mass

Just as Christ's interior offering of Himself was externalized in a

ritual oblation at the Last Supper, so is there an external, liturgical rite of the Mass.

The importance of this many-faceted exteriorization is brought out by Vatican II's Constitution

on the Liturgy.

As mentioned before, this exteriorization of

the internal oblation is according to man's social and corporeal nature. That it is in

harmony with the social part of man is evident from the fact that the external rite

assembles the People of God to worship together as a community. The individual members are

consequently enabled to help one another to achieve the proper worship of God. The Constitution

gives stress to this social aspect of the liturgy. It states that the very nature of the

liturgy demands that all the faithful be led to a full and active liturgical

participation. Such is in keeping with their vocation as "a chosen race, a royal

priesthood, a consecrated nation" (1 P 2:9). The Constitution emphatically

states that such full and active participation on the part of all the people is the chief

aim of the liturgical renewal.21

As also previously observed, the external rite

is likewise according to man's bodily nature. In the case of the Mass (and the sacraments

also) we observe that the very validity of the sacrifice depends on having the proper

materials for the offering – bread and wine – and on the use of the proper form

of consecration. The external, the ritual, the sensible, are indeed indispensable.

In all this we note the great law of

incarnation. The Incarnation established a set pattern for the redemption of the world,

redemption taken both objectively and subjectively. Christ redeemed the world through His

sacred humanity. This humanity is, then, the gateway to the divinity, to eternal life.

As Christ's created humanity was indispensable

for accomplishing the sacrifice of the objective redemption, so are created things

necessary for the eucharistic sacrifice of the subjective redemption. This fact calls to

mind the thought of Teilhard de Chardin. Teilhard holds a world concept in which all

things, natural and supernatural, spiritual and material, are united in a single and

organic unity. The pole of this unity is the person of the Incarnate Word, towards whom

the whole of creation converges.22 In such a concept the law of incarnation is

developed to the utmost, a fact brought out by the following words of Teilhard: "Let

us remember that the supernatural nourishes itself on everything."23

At various times in the history of Christian

spirituality, the Church has been plagued with an exaggerated spiritualism rising out of

various sources. Such a spiritualism, looking upon material things as more of a hindrance

than a help, is foreign to the true Christian spirit. A true theology of the Incarnation,

a theology which the Church so well concretizes in her liturgy, can lead to no other

conclusion.

It is no accident that a meaningful

incarnation spirituality is developing concomitant with the liturgical renewal. Although

we would not want to say that the incarnational element outweighs the transcendent element

in the Church's portrayal of the Christian life, yet she is leading the faithful of all

vocations to a deeper incarnationalism. The Church is accomplishing this through a variety

of ways. She is achieving this incarnationalism, for instance, through the great social

encyclicals, through the documents of Vatican II, and, in reference to our present topic,

through a revived liturgy.

There is a deep significance, and a rich world

of thought connected with the second sacrificial element of the Mass: the ritual oblation

which incarnates the interior oblation.

3) Immolation of the Victim

Christ, the chief victim of the Mass, has been immolated once and for

all in the offering of His own unique sacrifice. And yet, since the Mass is a true

sacrifice in its own right, we logically look for an unbloody immolation of Christ the

victim. Where do we find this immolation? Traditionally it has been seen to be present in

the double consecration of bread and wine. This double consecration symbolizes the

separation of Christ's blood from His body, and, consequently, symbolizes His death. Pius

XII's encyclical, Mediator Dei, states: "Thus the commemorative representation

of His death, which actually took place on Calvary, is repeated in every Sacrifice of the

altar, seeing that Jesus Christ is symbolically shown by separate symbols to be in a state

of victimhood."24 Jungmann reminds us of the importance of this

sacramental immolation of Christ. While admitting and even stressing the importance of

giving the "meal symbolism" its proper place in the Mass, Jungmann calls for a

priority of sacrificial symbolism: "It is quite another question whether or not it is

necessary or even correct to regard the meal symbolism as the decisive and fundamental

thing in the outward transaction of the Mass. If the Mass is a sacrifice then this must

find appropriate expression in the outward picture too; for sacrifice is essentially a

demonstrative action, the symbolic representation of inward readiness to give

oneself."25

Durrwell, a biblical theologian, also

highlights the importance of the Mass's immolation. He seems to say that Christ's

immolation is symbolized by the very words of consecration. He says that the Last Supper

and its commemoration, the Mass, are sacrificial meals. Consequently, ". . . Christ

appears in the victim state. He gives them to drink "the blood of the new covenant,

shed for many' (Matt, Mark), blood of sacrifice as the establishment of the old covenant

required (Exod xxiv, 8) shed at the moment of drinking."26

However, as we have said, Christ is not the

only victim of the eucharistic sacrifice. The members of His Body, the Church, are also

victims along with Christ. Those members must also be in a state of victimhood. As with

Christ, they cannot undergo a bloody immolation. Their immolation must also be a mystical

one. How is this accomplished? We can look to two passages of the encyclical Mediator

Dei for thoughts on such a mystical immolation. In one passage we read that pride,

anger, impurity and all evil desires are to be mystically slain. As the Christian stands

before the altar, he should bring with him a transformed heart, purified as much as

possible from all trace of sin.27 Positively considered, such a transformation

means that the Christian is striving to grow in the supernatural life by all possible

means, so as to present himself always as an acceptable victim to the heavenly Father.

In another passage of the same encyclical this

mystical immolation of Christ's members is further developed. To be a victim with Christ

means that the Christian must follow the gospel teaching concerning self-denial, that he

detest his sins and make satisfaction for them. In brief, the Christian's victimhood means

that he experiences a mystical crucifixion so as to make applicable to his own life the

words of St. Paul, "I have been crucified with Christ. . ." (Ga 2:19).28

Jungmann has a beautiful passage concerning

the Christian's eucharistic immolation. He states: "Every sacrament serves to develop

in us the image of Christ according to a specified pattern which the sacramental sign

indicates. Here the pattern is plainly shown in the double formation of the Eucharist; we

are to take part in His dying, and through His dying are to merit a share in His life.

What we here find anchored fast in the deepest center of the Mass-sacrifice is nothing

else than the ideal of moral conduct to which the teaching of Christ in the Gospel soars;

the challenge to an imitation of Him that does not shrink at sight of the Cross; a

following after Him that is ready to lose its life in order to win it; the challenge to

follow Him even, if need be, in His agony of suffering and His path of death, which are

here in this mystery so manifestly set before us."29

Summarily, then, we become victims with Christ

by lovingly conforming our wills to the Father's will in all things. Such conformity was

the essence of Christ's sacrifice, of His victimhood, and of His immolation. A similar

conformity must be in the victimhood and the immolation of Christ's members. This mystical

immolation is a lifelong process. The ideal is that each Mass participated in by the

Christian should mark a growth in his victimhood. The true Christian desires to die more

and more to all which is not according to God's will so that he may become an ever more

perfect victim with Christ.

4) The Father's Acceptance of the Eucharistic

Sacrifice

It has been observed that if sacrifice is to have its desired effect,

it must be accepted by God. That the Father always accepts the eucharistic sacrifice is

certain. For the principal priest and victim is Christ Himself, always supremely

acceptable to the Father. As for the subordinate priests and victims, they are, taken

together, the People of God, the Church herself.

There is always an acceptance on the Father's

part even as regards this subordinate priesthood and victimhood of the Mass. For even

though the Mass may be offered through the sacrilegious hands of an unworthy priest, there

is always a basic holiness in the Church pleasing to God. Because of such holiness the

Father always accepts the Church's sacrificial offering, for the Mass is the sacrifice of

the whole Church, and cannot be fundamentally vitiated by the unworthiness of any

particular member or members, even if that member be the officiating priest.

What do we say concerning the Father's

acceptance of the sacrificial offering of the individual Christian? Such an offering will

be acceptable in proportion to the Christian's loving conformity of will to the Father's

will. Speaking of the Christian's participation in the Mass, Jungmann says: "It

follows that an interior immolation is required of the participants, at least to the

extent of readiness to obey the law of God in its seriously obligatory commandments,

unless this participation is to be nothing more than an outward appearance."30

Having considered in successive sections the

immolation and acceptance elements of the Mass, we should consider the vital link between

these two. For just as the two are inseparably connected in Christ's sacrifice, so are

they also united in the Church's sacrifice of the Mass.

In Christ we equated the immolation of His

sacrifice with His passion-death, and the acceptance element with His Resurrection.

Uniting these two mysteries of death-resurrection, we spoke of Christ's paschal mystery.

We have seen that this mystery had been prefigured by the Jewish pasch and exodus,

component parts of the Jewish people's transition to a new and more perfect life. In the

case of Christ, we considered His pasch – His passover – to be a transition from

the limitations of His mortal life to the state of resurrected glory. We speak of Christ's

mortal humanity as having exercised limitations upon Him in this sense, that, although He

Himself was completely free from sin, He had exposed Himself to the conditions of a

sin-laden world through His human nature. In His death-resurrection He changed all this as

He conquered sin, as He redeemed us, as He passed to the state of glory with His

Father.

What happened in Christ also occurs in His

Mystical Body, the Church. The Church and Her members experience their own transition from

death to resurrection. The entire Church and the individual Christian express, through the

Mass, a willingness to grow in the participation in Christ's death. The Father accepts

this willingness and gives an increase in the grace-life, a greater share in Christ's

Resurrection. This process happened within a short span of time in Christ's life. In the

life of the Church it continually takes place until Christ's second coming. The Church,

with her grace-life of holiness, has already partially achieved her resurrection, but not

completely, even though she continues to grow in grace. St. Paul bears witness to this:

". . . but all of us who possess the first-fruits of the Spirit, we too groan

inwardly as we wait for our bodies to be set free." (Rm 8:23).

Vatican II's Constitution on the Church beautifully

portrays this fused state of death-resurrection which the Church in her members

experiences here below as she awaits the fullness of the resurrection in the world to

come: "For this reason we, who have been made to conform with him, who have died with

him and risen with him, are taken up into the mysteries of his life, until we will reign

together with him. . . While still pilgrims on earth, tracing in trial and in oppression

the paths he trod, we are anointed with his sufferings as the body is with the head,

suffering with him, that with him we may be glorified. . ."31

5) Partaking of the Eucharistic

Meal

The cycle of the eucharistic sacrifice is completed as the priest and

faithful partake of Christ the paschal lamb. The People of God have given Christ to the

Father. Now the Father gives Christ to the Church's members in the eucharistic meal.

Although the priest alone must communicate to assure the integrity of the sacrifice, it is

highly desirable, of course, that all present partake of the eucharist.

In the sacrifices of old, the victim of the

sacrificial banquet was considered in some sense divine by the fact that it had been

offered to the divinity. In the sacrifice of the new covenant we receive divinity itself

through the sacred humanity. With such a marvelous conclusion to the eucharistic

sacrifice, the fruits of Christ's sacrifice of Calvary are continually experienced.

There are other truths to be considered under

the paschal meal aspect of the Mass. One of these is the concept of the eucharist as sign

and cause of unity. Von Hildebrand comments on this: "All receive the one body of the

Lord, all are assimilated into the one Lord. Even if we leave aside the supreme

ontological supernatural unity which is realized here, the very act of undergoing this

experience represents an incomparable communion-forming power."32

Through the sharing of the one paschal lamb,

the Christian assembly has thus been vividly reminded of their oneness in Christ. Yet this

is a oneness in plurality. For each Christian is a member of the one Body of Christ in his

own unique way. He has been called upon to assimilate Christ according to his own

personality, vocation and graces. Consequently, just as the members of the People of God

are reminded of their unity at Mass, so are they made aware of their own uniqueness as

they depart from the eucharistic assembly, each carrying Christ to his own particular

environment according to his own individual personality.

We have considered the Church's eucharistic

sharing in the mystery of Christ according to a sacrificial structure. With the general

structure of the Mass established, we will now enlarge upon the concept of the

participation of the individual.

d) The Christian's Participation in the Mass

God has created man a social being. This fact has relevance as

regards man's salvation and perfection. Man does not go to God alone, but rather is saved

and perfected with and through others. This is evident in the study of salvation history

as one observes God communicating Himself to man in the framework of community. As we have

seen, this social dimension is also readily evident in the liturgy.

As we now discuss the individual's

participation in the liturgy, we in no way intend to underestimate the communal aspect of

the eucharistic sacrifice. We constantly presuppose it and its importance. Liturgy as

communal is the indispensable framework and background for any discussion of the

individual's liturgical participation.

Granted all this, it is still useful and

necessary to speak of the individual's participation in the Mass.33 Ultimately

it is the individual as individual who accepts or rejects God's offer of salvation and

sanctification. Therefore, to speak of the individual's response to God in the liturgy is

highly significant. Despite all the communal helps the individual receives in the liturgy,

despite the fact that the individual must always be deeply aware that he is a member of

the community, the People of God, it is still true to say that it is within the depths of

his own mysterious, individual personality that the Christian either becomes a mature

Christian through the liturgy or fails to do so. With such preliminary ideas established,

let us now consider the Christian and his role in the Mass.

1) The Baptized Christian and the Mass

Once again the reader is reminded that through baptism the Christian

becomes incorporated into Christ and His Church. Confirmation perfects this incorporation.

Although baptism incorporates us primarily into Christ's death and Resurrection, we again

stress that it also unites us with Christ in all His mysteries. This is so because all

Christ's mysteries are essentially one mystery, for none of them stands separately by

itself. Consequently, one cannot be initiated into Christ's paschal mystery without

simultaneously being incorporated into all of His mysteries.

The fact that all of Christ's various

mysteries are contained in the total mystery of Christ enables the Christian to encounter

the entire Christ in the liturgy. Mention of this fact brings us to our next point.

In baptism the Christian first encounters and

relives the mystery of Christ. He thereby receives a new life. But this life must be

nourished. The Christian must constantly re-encounter the mystery of Christ, and this he

does chiefly through the eucharistic liturgy. Here the Christian is daily privileged to

encounter Christ in the most intimate fashion. Here above all he exercises his priesthood

and consequently grows in supernatural vitality. We use the word exercise

purposely, since the liturgy is primarily an action, an exercise of the priestly office of

Christ.

Since the baptized Christian is sacramentally

participating in the mystery of Christ at the Mass, his priestly act must be modeled after

that of Christ's. This is true because the life of grace flowing out of the seals of

baptism and confirmation is structured according to certain modalities or characteristics

based on the life of Christ. This truth was developed at some length in the previous

chapter. There we stated that Christ, the head of the Mystical Body, has determined,

through His own life of sanctifying grace, the general lines of development according to

which His members' lives of grace grow and mature.

Therefore it is evident that the whole of the

Christian's life must be orientated to the Mass and be centered about it; for in Christ we

see His entire life centered around His priestly act of Calvary. This is true because His

interior sacrificial disposition, the essence of His priestly act, permeated everything in

His life.

The baptized Christian should also bring his

daily life, his whole life, to the eucharistic sacrifice. The Church which assembles about

the altar is not a nebulous, ethereal entity, but the Church of this earth. It is the

Church of men and women who are immersed in the work of this world. As they gather for the

eucharistic sacrifice, they are therefore not removed from the world of their ordinary

daily lives to an unreal world of ritual which has no connection with their temporal cares

and activities. Rather it is the reality of this ordinary daily life which they bring to

offer as priests and victims in union with Christ, priest and victim. In such a manner,

then, the eucharistic sacrifice looks to the past life of the Christian.34

Yet the Mass also looks to the future of the

Christian. By his participation in the Mass he receives grace to assimilate in a more

perfect manner the mystery of Christ. Ideally, each Mass participated in by the Christian

should mean that he leaves the eucharistic assembly with a greater Christ-likeness. Thus

he takes up his daily life as a more fervent Christ-bearer.

The Mass as it looks to both the past and

future embraces the Christian's entire life. It is meant to be lived each minute of the

Christian's life. Durrwell says: "The Mass is said in order that the whole Church and

the whole of our life may become a Mass, may become Christ's sacrifice always present on

earth. St. Francis of Sales resolved that he would spend the whole day preparing to say

Mass, so that whenever anyone asked what he was doing, he might always answer, 'I am

preparing for Mass'. We also could resolve to make our whole lives a participation in the

divine mystery of the Redemption, so that when anyone puts the question to us, we can

always answer, 'I am saying Mass'."35

2) The Mass lived out

As the Christian lives out the Mass, he is consequently daily laboring

with Christ in furthering the work of the subjective redemption. This is so because

Christ's sacrifice was a redemptive act, and the Church's reliving of this act in the Mass

is also redemptive. In this regard we must remember that the entire universe – not

merely man – has been redeemed. The nonrational and rational world alike await the

furthering of the redemption. St. Paul tells us: "From the beginning till now the

entire creation, as we know, has been groaning in one great act of giving birth; and not

only creation, but all of us who possess the first-fruits of the Spirit, we too groan

inwardly as we wait for our bodies to be set free." (Rm 8:22-23).

How does the Christian help Christ redeem the

world? (Henceforth the term "world" is to be understood as including both

rational and nonrational creation.) As previously stated, the Christian helps Christ

redeem the world by reliving Christ's mysteries. The same "events" or mysteries

which accomplished the objective redemption further the subjective redemption also. Since

at the heart of Christ's mysteries are His death and Resurrection, it is especially these

that the Christian must relive. As the Christian dies mystically with Christ through

loving conformity with the Father's will, he rises with Christ to an ever greater share in

the Resurrection, in the newness of life, in the life of grace. As the Christian in this

manner relives the paschal mystery of Christ, he is accomplishing not only his own

redemption, but he is also, in a mysterious yet real manner, helping Christ redeem the

world.

Although Christ's life was summed up in

death-resurrection, it also included various other "events" or mysteries. Each

of these in its own manner contributed to the redemption. So it is with the Christian's

life. His participation in Christ's death-resurrection must be "broken down"

into the other mysteries of Christ's life.

The Christian must always remember that he

carries away from the Mass not only the Christ of the death and the Resurrection, but

also, for example, the Christ of the hidden life and the Christ of the public life. As the

Christian lives out his Mass in the exercise of his Christ-life, all these various

mysteries should therefore be present.

Before we give examples of how the Christian

can relive these saving events of Christ's life, it is well that we first distinguish the

two different levels on which the Christian assimilates the mystery of Christ.

Christ, through His death and Resurrection,

has transformed us. This transformation is a "new creation," a new life of

grace. Through our baptism we are initiated into this life and consequently we exist as

new creatures. As long as we possess the life of sanctifying grace, which is our share in

the mystery of Christ, we are living according to this new existence whether or not this

life here and now incarnates itself in a concrete, supernatural act. In this sense the

life of grace, the "new creation," is fundamental, radical and transcendent, a

share in the transcendent holiness or mystery of God Himself.

However, God expects that our life of

transcendent holiness incarnate itself in concrete supernatural acts. It is in this

respect that we speak of reliving the various mysteries of Christ through specific

supernatural attitudes and acts. This may also be called imitation of Christ, but with a

certain precaution, namely, that the imitation in question is to be considered primarily

as interior rather than exterior. By this we mean that although the Christian can to a

certain extent imitate Christ according to what was His external mode of conduct, it is

primarily through adopting the mind of Christ – His interior dispositions – that

the Christian puts on Christ. With this said we now offer suggestions as to how the

Christian relives the mysteries of Christ whose presence and transforming influences have

been encountered in the eucharistic liturgy.

For instance, each member of Christ, whether

he be bishop, priest, religious or layman, can accomplish much of his redemptive work by

an intense reliving of Christ's hidden life. Certainly our heavenly Father would have us

learn a great lesson from this fact, namely, that His Christ lived out so many years of

His earthly life in a hidden manner, doing the ordinary tasks of the ordinary man. In

assimilating this particular mystery of Christ the Christian must say with Rahner:

"Let us take a good look at Jesus Who had the courage to lead an apparently useless

life for thirty years. We should ask Him for the grace to give us to understand what His

hidden life means for our religious existence."36

Christ did not lead only a hidden life, but a

public life also. All vocations within the Church are likewise called upon to reproduce

this part of Christ's life in some manner. One aspect of Christ's public life that should

be common to all Christian vocations is the selflessness, the constant concern and love

for others which Christ constantly and vividly displayed. This concern for others cost

Christ much in fatigue of body and mind. Nevertheless, He continuously gave Himself

completely to others.

Another characteristic of the public life

which all can imitate is that of Christ as witness. Here, then, we reemphasize within our

present context that which was stated in an earlier chapter concerning the Church's

continuation of Christ's prophetic role. Christ was a witness to the Father, a perfect

manifestation of the Father's truth and love. He bore this witness not only through His

formal teaching but also through His actions, His attitude, His gestures. All members of

Christ are called to give witness also. The Christian's entire life should be a witness to

the truth he holds. The world comes to know Christ through the Christian. Schillebeeckx

comments on this aspect of being witness: "Our life must itself be the incarnation of

what we believe, for only when dogmas are lived do they have any attractive power. Why in

the main does Western man pass Christianity by? Surely because the visible presence of

grace in Christians as a whole, apart from a few individuals, is no longer evident."37

St. Paul sums up the redemptive work of Christ

under the mysteries of death-resurrection.38 These are the principal mysteries

which the Christian must assimilate from the eucharistic liturgy and reproduce in his own

life. More and more the Christian spiritual life is being considered as a process of

death-resurrection. It is obvious why this is so, for if Christ's entire life was summed

up in His death-resurrection, so also is that of His members.

Christ's death and Resurrection are so closely

united that they are two facets of one mystery rather than two separate mysteries.39 It

is likewise with the Christian. The death aspect of his supernatural life is intimately

connected with his life of resurrection, and in various ways. For instance, his very life

of grace is his life of resurrection, but his continual growth in spiritual death –

death to selfwill in all its numerous manifestations – is achieved through grace.

Consequently, the Christian's life of resurrection always accompanies his life of death.

We also see the two connected more obviously in the sense that a growth in the death

element always results in a growth in the resurrection element.

The daily life of the Christian, then, is a

combination and antithesis of death-resurrection. As he gives himself in love to the

Father's will, manifested to him in so many ways, the Christian is achieving both death

and resurrection. Christ's ultimate goal, as man, was His Resurrection. Resurrection, a

greater share in the divine life through grace, is also the goal of the Christian.

These few remarks give examples of how each

member of the People of God is called upon to relive Christ's entire life as centered in

death-resurrection. More could be said. But we think our remarks have sufficed to indicate

how the Christian is to live out these various mysteries of Christ. Moreover, let it be

recalled that all the mysteries ultimately make up the one mystery of Christ.

What we have said thus far applies in general

to all vocations. But since there are different vocations within the Church, we must also

say that each of these projects Christ in a somewhat different manner. Each Christian must

study how in particular he is called to put on Christ. Essentially, of course, all put on

Christ in the same manner. Yet there are accidental differences according to the vocation,

work and individuals involved. For instance, the lay person, in general, is called to a

deeper involvement in temporal affairs than is the religious.

Each member of Christ, according to his

particular vocation, work and personality, has something special to take away from the

Mass.40 Each Christian, as he lives out the mystery of Christ, projects Christ

to the world in his own way. Each Christian, as he himself grows in Christ-likeness, is

also helping Christ to redeem the world in a manner commensurate with his total Christian

person. For holiness is necessarily apostolic whether the Christian at any particular time

is engaged in an external apostolate or not.

Each Christian, according to God's plan for

him, must have a vital and dynamic desire to help Christianize the whole world. Perhaps he

can do very little through direct, external apostolate. But his prayers and sacrifices

– indeed, his entire life – can touch the whole world. Through an intense

Christian life the individual can help Christ further the redemption of the family, the

business world, the social structure and the like. The Christian is called to have this

deep desire: to see the whole universe imprinted with the name of Christ. How true it is

to say that the Christian's vocation, rooted in the liturgy, calls for deep involvement in

this sacred activity.41

In schematic outline we have discussed the

manner in which the baptized Christian extends his Mass to his daily existence. As he so

lives out his Mass, he is becoming more Christlike. He becomes a more perfect priest and

victim for his next participation in the eucharistic sacrifice.42 The beautiful

cycle which the Mass contains lies exposed before us. As part of this cycle the Christian

is intimately involved in the process of continued redemption. The Mass is the

center of the Christian life: ". . . the liturgy is the summit toward which the

activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the fount from which all her

power flows."43

Mary's

Message from the Rosary of August 27, 1996

Mary's

Message from the Rosary of August 27, 1996